|

"To such a state of affairs it is convenient to give the name of progress. No one confessed the Machine was out of hand. Year by year it was served with increased efficiency and decreased intelligence. The better a man knew his own duties upon it, the less he understood the duties of his neighbour, and in all the world there was not one who understood the monster as a whole. Those master brains had perished. They had left full directions, it is true, and their successors had each of them mastered a portion of those directions. But Humanity, in its desire for comfort, had over-reached itself. It had exploited the riches of nature too far. Quietly and complacently, it was sinking into decadence, and progress had come to mean the progress of the Machine." - The Machine Stops E. M. Forster Franz John

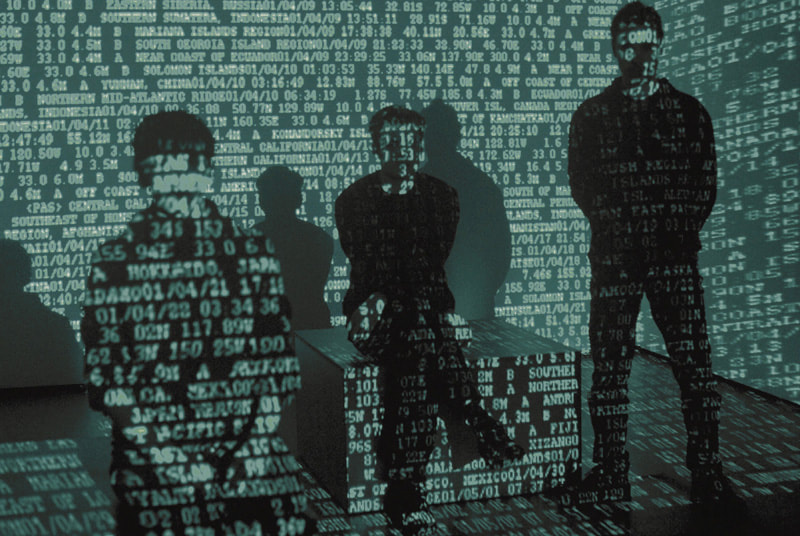

Turing Tables An Untitled Composition for Tectonic Spaces "Several million earthquakes of different intensities occur each year. Seismological institutes throughout the world measure these vibrations and exchange and communicate this collected data among themselves via automated internet-transfers. It is this meta-perception that Franz John makes visible in his project “Turing Tables,” siphoning this human-machine-communication data stream directly from finger-servers and bringing it into his online installation. In a matter of seconds, this installation converts these measurements from the seismological stations into sound and image. From the perspective of a "global eye" the internet directly connects the observer with the pulsating core of the earth. This project is therefore not about the catastrophes that cause these movements in inhabited areas, but instead about the archaic feeling and consciousness that the earth is an organism, that it moves and that it can be understood as an organism in constant flux. “This artistic realization is based on the machine-theory of the mathematician Alan Turing, wherein my interest is not in the number-chain itself but rather in the tectonic forces and energies of a matrix which is visibly and continually updating and renewing itself.” A project in collaboration with sound artist Ed Osborn (Oakland, CA) and Sascha Brossmann (Berlin, Germany)." Interview with Dr. Ian Bogost

AM: When I saw A Slow Year, I didn't know how to use an Atari. I had never used one in my life. In a video of you discussing your teaching strategies, you say that you have your students create a text adventure game partly because they are unfamiliar with the medium. What do you think the use of aged and/or unfamiliar gaming platforms brings to the table? IB: The strangest, most tragic thing about technology is that it dies, and that we let it. Nobody would think twice about using an 8x10 view camera, like Ansel Adams sometimes did, in order to produce new photographic images. You’ve got paintings in your portfolio that deploy pigment on board, like painters have done for a millennium. Computer technologies, and others, are not really that different from any others, apart from the fact that we mistake their unique, material properties for mere advancement, simple progress. Instead, it’s possible to treat those old, “dead” platforms as living ones, which have their own unique and distinctive aesthetics. That’s what has always interested me about the Atari. It’s a weird computer whose design is unlike any other before or since, and which creates distinctive affordances and constraints that impact the work made on it—like the influence of the horizontal scan-lines on the visible picture. AM: I have found so far in my early life that my interests have not really changed, only grown. I have been interested in the natural world in relation to the digital world for my whole life, and those interests have always been there. Have you always been interested in the themes that you are exploring in your work? IB: At a high level, yes. The place where technology and human culture meet. But that doesn’t feel like much of a distinction, anymore. But within them, my focus has swayed and shifted and evolved over the years. My early work was extremely plain in its political tenor. Now it’s much more expressive and formal. One thing that’s harder to think about when you’re younger is that everything you do ends up making sense to you, because you are there inside your body the whole time, while it’s happening. It all makes sense to you, because you were there. Sometimes people will ask me, “How did you move from studying poetry to videogames?” But if you look at a project like A Slow Year, the answer is obvious: there was no move. Nothing changed. That was me the whole time. AM: How has teaching impacted your work? IB: Teaching is one of the only things you can do where you get immediate results, whether positive or negative. You can see the work happening immediately, and at scale, in a studio or a lecture hall, which is an enormous gift. It’s like having your own personal focus group, where people from different backgrounds, many young, offer their perspective on things. Hard to overestimate that value, in orienting you toward what works, what doesn’t, what’s important, what’s not. It’s like having a little spacetime-compass in your pocket. AM: What advice would you give to your undergraduate self, if you could? IB: Consider specializing more than you have, without giving up too much breadth. Take more risks, but considered ones, before it’s harder to do so. Remember that you will never have as much time and freedom as you do now. Strike the trends that are contemporary, because soon they will evolve into history, and also you will become exhausted sooner than you expect. Eat better. Sleep at night. AM: What would you say is your relationship to the contemporary art world? IB: Troubled. If you want a surefire way to take one or two zeroes off your art, making video-game art is a surefire way to do that. The games (and tech) world aren’t necessarily interested in the art world, and where they have begun to become so, the result is often disorienting (one example, which I wrote about last year: https://www.theatlantic.com/ technology/archive/2019/03/ai-created-art-invades-chelsea-gallery-scene/584134/). As someone who exhibits and sells art, and whose work is held in some important and prestigious institutional collections, I still don’t think of myself as an “artist” primarily, let alone a working one. Sometimes that’s a relief, sometimes I am jealous of my friends who have a clearer relationship to it. AM: Do you think that art is capable of inspiring political change? IB: Yes, but I’m not sure that’s saying much. A good lunch can probably inspire political change, or a bad one. The difference between art and politics is that politics involves action, and art involves symbol-making. Symbols help us motivate action, but they almost never do so in some kind of direct or even traceable way. They incorporate themselves into our beings and then we have to process and muster them in relation to specific action. Often, the least political art is the art that is overtly political, rather than the kind that really deeply synthesizes an idea, such that the viewer can grasp it in a truly novel way, and use that new knowledge for action and change. AM: In 2004, you incorrectly predicted that every major candidate in the 2008 US Presidential elections would have their own PlayStation 3 game. Today, there is a Kickstarter for a "Bernie's Journey" RPG videogame. There is also a "Bernie Arcade" game, which is very similar to Flappy Bird, except with Sanders' face plastered over a plane. Do you think there is still potential for future presidential candidates to use video games in their campaigns? IB: No and yes. No because the media ecosystem has shifted so completely since then. Back in 2004, we didn’t have smartphones. We didn’t have social media. Or YouTube. Everything was different, and the way people might have created and exchanged ideas with computers was still open. But since then—a duration of time that might encapsulate the majority of your whole life, I’m guessing—we developed different habits. It’s hard for me to imagine games making headway against those currents, which are very strong. But yes because anything’s possible. It just might take another big shift in the technological landscape. AM: What are you working on right now? IB: As far as art goes, I’m working on a new Atari project. I’ve always been obsessed with the abstract, naturalistic style of Atari games, and the way it gets expressed in those scan-line-oriented horizontal lines. So I wrote some software that lets me make abstract, Atari landscape paintings, and I’ve built a kind of en plein air Atari rig that I can take into the field, anywhere. Now I’m working on a robotic apparatus to “output” those works as oil pigment on board. My goal is to try to split the lane between games and art, using the games technology but producing a traditional fine-art artifact. |

This journal documents my research relating to the animal in digital media since the 1970’s, which marks the birth of the environmental movement and the start of the digital age.

Archives

November 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed